Anne Scheiber worked as an auditor for the IRS. She retired at the age of 51 in 1944, and focused on managing her portfolio for the next 51 years of her life.

I wanted to share with you the story of Anne Scheiber, who died at the age of 101 with a portfolio of dividend stocks worth over $22 million. That portfolio was generating over $750,000 in annual dividend income at the time of her death. Anne Scheiber is

one of the most successful dividend investors of all time.

I believe that this story can be inspirational to many. After reviewing it, I can tell you that I understand

the blueprint for financial success. One can easily see the steps taken to achieve financial independence, so that they can mold their lifestyle in a way, shape or form that they desire.

There are several lessons that we can all learn from:

1. Invest in leading brands in leading industries

2. Invest in companies with growing earnings

3. Capitalize on your interests to uncover investment opportunities

4. Invest regularly

5. Reinvest your dividends

6. Never sell your stocks

7. Keep informed on current or future investments

8. Invest in a tax efficient manner

9. Give something back to society

10. Be frugal

This set of core principles can help anyone who commits to it to end up with

a million dollar dividend portfolio.

Anne was raised by her mother, after her father had passed away after losing money on real-estate investments. She had started working as a bookkeeper at the age of 15, and started working at the IRS 27 years later. At the time, families prioritized higher education for theirs sons. This meant that Anne had to persevere and go to school on her own dime. She invested in herself and graduated from night school, and ultimately passed the Bar. Despite being very well qualified, and despite her excellent job performance, she realized that as a Jewish woman she will not advance much professionally. Because of the discrimination at the time, she was never promoted and never earned more than $3,150/year after 19 years at the IRS. She had a difficult life all her life, where she had to fend for herself, which probably led her to determine that the best way to achieve a mark on this world was through investing. She knew, decades before her death, that her nest egg should be earmarked for charity.

“She’d say, ‘Someday, when I’m long dead, there will be some women who won’t have to fend for themselves.’

Anne Scheiber may not have earned a high salary, or earned promotions, but she learned a lot at her job. She learned that the rich tend to invest in appreciating assets that paid cash flows. If you spend any time reviewing tax returns, you will soon realize that wealthy people tend to own a lot of stocks that pay dividends, real estate that pays rent and businesses that generate income for their owners. This was the a-ha moment that inspired Anne to build her wealth through blue chip investing. The lesson she learned poring over other people's tax returns was that the surest way to get rich in America was to invest in stocks.

According to some stories, her portfolio was valued at $5,000 at the time of her retirement. Other stories discuss older tax returns from the 1930s that showed annual dividend income of $900, which also increased over time. It is possible that her portfolio at the time of retirement in 1944 was close to $18,000 - $20,000, implying a dividend yield of 4.50% - 5%. Never the less, I still find it impressive that she left $22 million to charity at the time of her death 51 years after retirement. All of this initial capital was a result of her savings from a long professional career, at a time when few Americans owned stock. It is even more impressive, given the fact that she lost money investing in the stock market, after a brokerage firm through which it did her business collapsed in the 1930s, taking her money with it. This was before SIPC insurance protections. However, Anne Scheiber bounced back and kept at investing for the rest of her life.

According to her attorney, she had a very high savings rate, which is how she was able to accumulate her starting capital to build her nest egg. She saved something like 80% of her salary, which is impressive.

Her largest positions from 1995 are listed below:

Her portfolio included stakes in over 100 companies, most of them well known names such as Coca-Cola, PepisCo, Schering-Plough, Bristol-Myers, etc. She bought companies in industries what she understood, such as pharmaceuticals, beverages and entertainment.

Anne focused on companies with leading brands that grow earnings over time. This ensured that the business can pay more in dividends and increase intrinsic value.

Her strategy was buying in stock regularly, and holding for decades. This let her take full advantage of the power of compounding. She never sold, because she hated paying commissions. This was another smart move, which let her take full advantage of any outsized gains. Letting winners run for decades is what separates the best investors in the world from those who have mediocre investment careers. Very few people have the patience these days to hold on to stocks for months, let alone decades. But this patience is a trait that separates winners from losers, because it gives companies time to compound profits, dividends and intrinsic values. As you and I are well aware, sometimes companies go nowhere for a while, which causes many investors to give up and sell, right before things start turning around. By becoming a patient long-term investor, you are well positioned to take advantage of the few outsized winners in your well diversified portfolio.

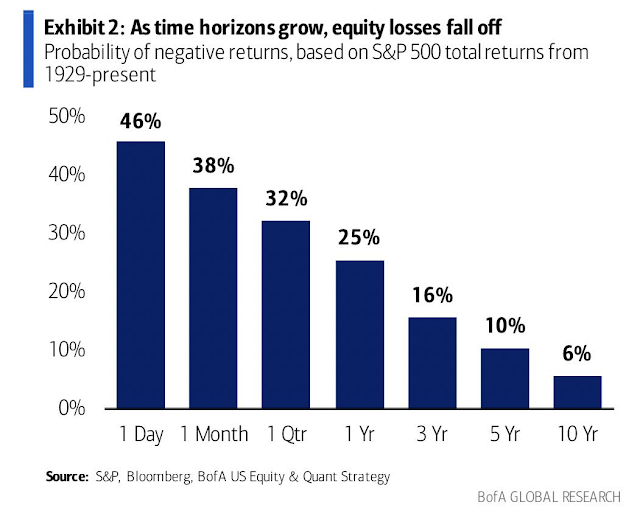

Being a patient long-term buy and hold investor is beneficial during bear markets, when share prices fall by 50% or more. Many get scared by these temporary quotation losses, and sell in a panic. Smart investors hold on tight, and even add to their positions if they have capital available for deployment.

When you never sell your stock, you also never have to pay taxes on long-term capital gains. If you leave your portfolio to charity, there is no estate tax either. I am pretty sure that Anne enjoyed knowing that IRS will see a small fraction of her estate in the form of taxes.

Finally, she reinvested her dividends, which helped further compound her capital and income. In the 1980s, she started investing her sizeable dividend income into municipal bonds, which paid 8% annual tax free interest. Her annual investment income of $750,000 was a mixture of dividends and earnings.

Since Anne didn’t get promotions and raises, she ended up cutting expenses to the bone. She understood

the simple math behind early retirement. When I read comments about Anne, they all focus on her extraordinary frugality. She lived in her rent-controlled apartment for 51 years after retirement, wore old clothes, and scrimped on spending for food. Her entertainment involved going to the movies, reading stock reports and researching companies and reading. She never married or had children. While it is a little extreme even to my tastes, I do think that you can learn from everyone and try to apply those lessons to your own life.

When I read about her story, I learn that long-term investing in leading companies that grow earnings is paramount to success. I learned that buying these companies over time, and building a solid diversified portfolio can help soften the blows of the ones that fail. But it also provides the opportunity to discover the next great company as well. Diversification and long-term investing work wonders for those who are patient enough to compound their money for decades. I also like the idea that investing is the only field where if you are good, your race or gender or nationality do not matter, as it is a true meritocracy. And if you keep your money invested long enough, you will be able to end with a lot of money at the end of your life. I also keep learning that many successful investors tend to live to an old age. Perhaps that’s because investing in stocks is a very stimulating activity, because it requires constant research, learning new facts and ideas and discarding old facts and ideas that do not work or are flat out wrong.

A lot of the negative comments towards Anne generally come from people who do not understand

the power of compounding and getting rich late in life.

As I mentioned above, Anne was very frugal, and she managed to save 80% of her salary to end up with her investable nest egg. She had to fend for herself all her life, so that little nest egg was her way of regaining her independence from a world that discriminated against her. It was to allow her to live her life on her own terms, which is admirable. If she lived today, she would have likely found a lot of friends in the FIRE community. Her nest egg provided some F.U. money to her, away from a judgmental society and bosses.

It is likely that she compounded money at roughly 14% - 15%/year for a long period of time. As I discussed with the story of Ronald Read, when you compound money for a long period of time, and you compound it at a high rate of return, the initial amount you had is really small relative to the amount end up with.

I ran a simple calculation where I compounded $20,000 at a flat 15% compounded rate of return for 50 years. I also assumed that her portfoolio yielded a flat 3%, just for illustration purposes. In reality, dividend yields were closer to 4% - 5% at the beginning of her journey in the 1940s, and went all the way down to 2% - 3% in the 1990s. She did start reinvesting dividends into municipal bonds in the 1980s, but my calculation is not accounting for it, since it is for illustrative purposes, trying to help you understand the nature of compound returns. You can

download my calculations from here. This is a summary of compounding:

This means she had $20,000 in 1944, and earned $600 in annual dividend income

Her portfolio grew to $80,900 by 1954, and earned $2,427 in annual dividend income

Her portfolio was worth $327,330 by 1964, and earned $9,820 in annual dividend income

Her portfolio grew to $1.324,000 by 1974, and generated an annual income of $39,700

By 1984, her portfolio was worth $5,357,000, generating $160,700 in dividends

By 1994/1995, her portfolio was worth $22,000,000, generating $750,000 in dividends

So if we assume she started with $20,000 in 1944, that money may have generated something like $1,000 in annual dividend income for Anne. If she really saved 80% of her salary of $3,150 in 1944, that dividend income was enough for her to live off. But that also meant she had to be frugal to survive. I am not sure if she had a pension or Social Security check, but that was likely to be a small amount that was not accessible until the age of 62.

I am going to make the assumption that she compounded her money at roughly 15%/year, starting from a base of $20,000 in 1944. It is possible that her actual returns were closer to 12%/year, and that she started from a higher base when she retired, due to her high level of savings. It is also possible that she saved money from her pension or social security as well, and added to her investments. Unfortunately, with most of these stories, we do not get the complete accounting, just bits and pieces from which to connect the dots.

If she really compounded money at 15%/year however, that means her nest egg doubled every 5 years or so. Of course, compounded stock market returns are not a linear 15% - sometimes the returns at the beginning of the journey are higher than the returns at the end of the journey. I would assume that Anne’s nest egg didn’t even start producing enough dividends to replace fully her salary until a decade into her retirement. By that time her frugal habits had already been established and she was in her 60s. The average life expectancy for a female in 1943 was 64 years, and by 1960 this had increased to 73 years.

If she had lived to the age of 65 or 70, her nest egg would have been high at around a quarter of a million, but not high enough to even write about.

I would assume that she didn’t even become a millionaire until the early 1970s, when she hit 80. After the 1972- 1974 bear market, she may have lost the millionaire status, only to regain it by the 1980s bull market. It is just pure mathematical fact that if you start with a decent amount of money, compound it at a decent rate of return and you compound it for a long period of time, you will end up with a lot of money. Probably more money than what you know what to do with. But if you have $22 million at the time of your death at 101, that doesn’t mean you had that $22 million when you retired at 51. You probably only had around $20,000 or so. This is a lot of money, especially given that the dollar in 1944 bought more than the dollar in 2020. But it is nothing earth-shattering either.

It is fascinating to me that a lot of people fail to understand the role of compounding for long periods of time, and getting really rich in life. Yet, they are happy to read about Warren Buffett, and praise him. Yet, both Buffett and Anne Scheiber probably had similar money personalities that liked doing what they liked doing, and kept doing it for long periods of time.

To put things in perspective, Warren Buffett was worth around $400 million at the age of 52. At the age of 90 he is worth $78.40 billion. He did have a lot of money at the age of 52, and compounded it at a very high rate of return for almost 40 years.

Anne's insight that the easiest way to get rich in America is through stock ownership is widely supported by research and data that is available to us today. There was little research in the past about the advantages of equity ownership, and this research was not as popular as today.

If you put $1 in US stocks in 1802, and compounded at 8.10% annualized return for the next 211 years, you would have ended up with $13.50 million by 2013. If someone placed a small amount of money in stocks so long ago, and never spent it, they would be very rich. Or rather their descendants.

This brings me to another concept. While a typical career lasts 30 – 40 years, a typical retirement could also last 30 – 40 years. That nest egg has to provide for a retired couple, one of which will likely outlive the other. If we really think about it however, many parents want to provide a solid base for their adult children and even grandchildren. As a result, a typical retiree may have to plan for more than 30 – 40 years. They may have to think about a bullet proof strategy that would deliver dividends for 50 years or more. That may be even more imperative, if you plan to live money in a trust for the use of a charitable cause. Most charitable causes require support in perpetuity.

Today, we learned the story of Anne Scheiber. She was a frugal investor, who built an impressive portfolio worth $22 million and generating $750,000 through a combination of:

- Frugality to save her initial investable capital

- Regular investing over time in companies she understood

- Buying strong brands names that grew earnings and dividends

- Staying the course for the long run, and ignoring stock market fluctuations

- Patiently compounding capital and income for 50 - 60 years

Thank you for reading!

Relevant Articles:

-

Profiles of Successful Dividend Investors

-

The Simple Math Behind Early Retirement

-

This Is How This Successful Dividend Investor Turned $1,000 Into $2 Million

-

The Most Successful Dividend Investors of all time

-

How to Become a Millionaire

-

The million dollar dividend portfolio for retirement