As an investor, I am aware that I have a lot of blind spots. Someone with a glass half full outlook on life might say that I have a lot of room for improvement though.

I do believe that successful investment is about continuous improvement, which is only possible through active learning. That includes reading books, articles, journals but most importantly also doing the heavy lifting and actually investing money. It’s very helpful to have a process that helps in most aspects of the investment process:

1. Identify the population

2. Define the traits you are looking for

3. Define the entry criteria that would trigger an investment

4. Define exit criteria that would cause an investment to be sold

5. Manage risk

Naturally, I like to study other investors and their strategies. At least based on what I see publicly.

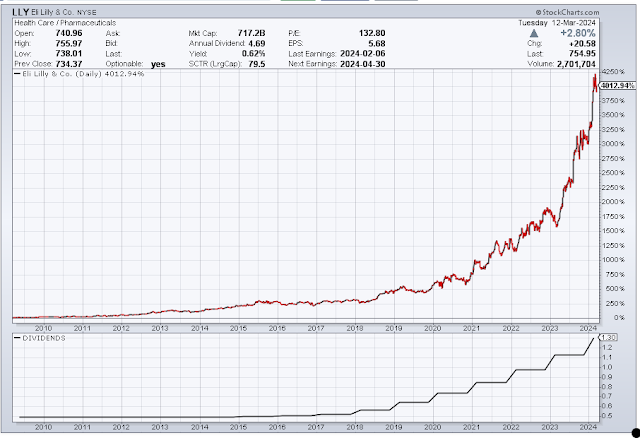

I recently saw that Eli Lilly (LLY) has become one of the largest companies in the US. A lot of investors are salivating over the past 15 years of returns. Yet I doubt most are even aware that this is a dividend stock, and/is/has been a dividend growth stock as well.

The question I have on my mind is: How would one have identified the company as an investment 15 years ago, and would they have actually bought it?

Naturally, I remembered how Eli Lilly was a dividend aristocrat about 15 years ago or so, with a 40+ year history of annual dividend increases under its belt. The stock sold for 8 times forward earnings in 2009 and yielded about 6%. It had suffered a terrible decade, as earnings were largely flat, and the stock price had nosedived by 60% from its highs in the year 2000. Naturally, the P/E ratio had shrunk significantly too – from 30 - 40 in late 1990s to 8 in 2009.

You may like my review of Eli Lilly from 2009, back when things were at their bleakest it seems like.

An investor who bought in 2009 for the dividend and stayed, did pretty well. They were getting paid a generous dividend to hold on to a dividend aristocrat. Those sleepy companies can sometimes also surprise on the upside, by uncovering a blockbuster drug in their pipeline. It’s like having your cake and eating it too. It’s not so easy to predict years in advance what or whether the pipeline that takes billions of R&D will produce a blockbuster drug or a series of failures. Still, it’s a nice option on the future, while getting paid to wait.

The company did not really show growth in earnings per share between 1999 and 2009 however. So this shows like it was an unlikely candidate for purchase at the time.

There were a lot of other candidates in 2009 that have done well, whose earnings patterns seemed much more promising (and stayed promising). Those include the likes of Sherwin-Williams, S&P Global (Then McGraw Hill), Cintas, ADP, Grainger, etc. You may like this article from 2008, called "Best Dividend Stocks For the Long Run"

Earnings per share for Eli Lilly were largely flat from 1999 to 2016. The stock is highly unlikely to have been picked up by my process too. Right now it’s simply overvalued.

The company was a dividend aristocrat however. But the dividend growth indexes like the Achievers and Aristocrats that would have held it through 2010 actually sold it at the end of 2010/early 2011. The company had become a dividend achiever in 1977 and a dividend aristocrat in 1992.

However, the company was dropped from the dividend aristocrat and dividend achiever indices in 2011, after it failed to increase dividends in 2010. This means that all the passive dividend ETFs holding it were forced to sell the company.

Despite not raising dividends between 2010 and 2014 however, the company never cut them. It started raising them again in 2015. So someone who had bought it because it was a dividend achiever/dividend aristocrat, and didn’t sell due to the dividend freeze would have come out ahead on this one. Of course, they could have also bought it much earlier, such as the 1990s for example. However they would have had to hold through the 2000 – 2009 period, which would have tested their conviction.

The only ones that probably owned it in 2009 and are likely to have owned it through today are your basic index funds on S&P 500 and/or Total Market. Of course, they also held it during the lost decade of 1999 – 2009 as well, when returns were negative.

It’s actually fascinating to study those index funds, because they take long-term buy and hold investing to the next level.

They make a lot of bets, and then they stick to them through thick or thin. They allow the power of compounding to do its magic, and basically never sell. (or at least rarely do).

This allows the best investments to mushroom, and deliver the lions share of profits for truly long-term investors. As we have witnessed before, constant tinkering and turnover are counter-productive and costly, as they detract from returns due to fees, costs, taxes and opportunity costs (e.g. selling winners to buy losers).

As a result, a small number of companies tend to drive total returns forward. The losers become a smaller and smaller portion of the portfolio. Even if they went to zero, there are some huge winners that not only pay for them, but also turn a net profit overall.

This is basically the Pareto Principle in action.

Nobody knows in advance for sure which those winners would be. This is why it’s important to hold that diversified basket through thick or thin, and just stay invested. Second guessing yourself, and trying to pick the winners from the losers is definitely hard. Mostly because it is very hard to predict for sure. Predictions are hard, especially the ones about the future..

Naturally, this gets you thinking. If you missed out on these exceptional winners, your portfolio would likely deliver substandard performance.

Missing out could happen in two major ways actually.

One of the ways you could miss out is because you didn’t buy the stock. Perhaps due to omission, perhaps due to your process missing something or perhaps because the stock did not look investable then. Perhaps it became investable later, but by that time you either missed it because you weren’t monitoring it or because by the time it became investable the stock price was already high enough and recovered to reflect that.

Another of the ways you could miss out is because you sold the stock.

After studying index funds for a while, I’ve come to the conclusion that it does make sense to hold a lot of companies by placing small bets on them and then holding them. This lets you own a lot of companies, and you would likely profit overall, without even knowing or having to need to have a crystal ball. You have small turnover, which is mostly driven by companies being delisted due to acquisitions/mergers/bankruptcies/delisting (at least looking at the broad total market index that is). Just buy and hold. By not caring about valuation as well, they are less likely to pass on to promising companies merely because they sell at say 25 times forward earnings and not 20 times forward earnings. On the flip side of course is that they may end up overpaying for future growth, dearly. Of course there are trade-offs with everything. The issue of this buying the whole haystack theory is that you have a lot of good businesses mixed in with a lot of bad businesses as well.

Of course, you do not need to buy every company to make money in equities. Having a process to select a group of quality companies, and hold on to them through thick or thin can deliver good results.

This brings us back from the world of broad index funds to the narrow world of dividend funds.

High turnover is one issue with dividend ETFs.

They actually sold out of Eli Lilly in 2011, which basically reduced their returns.

My lessons from this exercise is to try to work and design portfolios that hold a lot of companies, which rarely sell.

When it comes to the dividend growth investing universe, it apparently takes sense to take a lot of bets, and stay invested with them. An improvement over regular dividend ETFs is to not sell if a company fails to raise dividends. However, it is still likely a good idea to sell if a company cuts/suspends dividends. If a company is acquired, one has to sell regardless.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you should ignore quality as well. Taking lots of bets is fine, but at some point there are also companies that are not doing well financially. They may turn around, or not. But speculating when the date is not supporting speculation is still speculation.

That being said, no process is going to be perfect.

There is always going to be room for improvement.